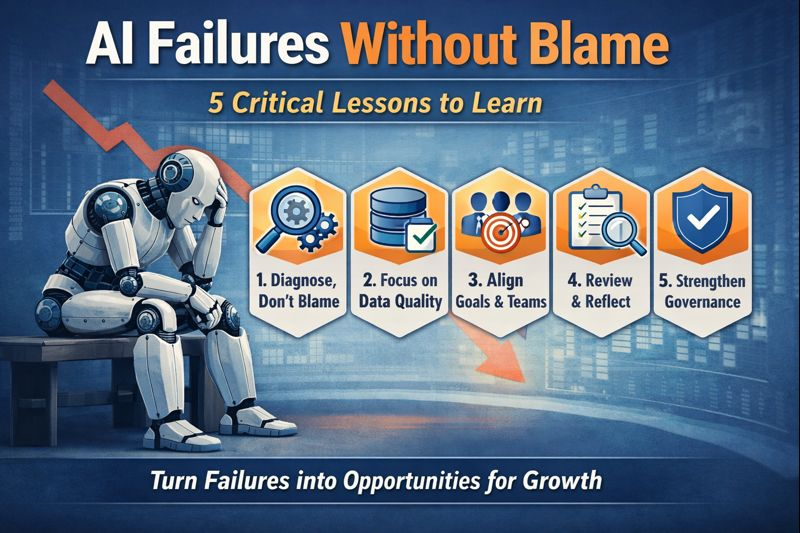

AI Failures are no longer rare edge cases or isolated project mishaps. They have become a defining feature of the current phase of AI adoption, where ambition often outpaces organizational readiness. Across industries, enterprises are investing heavily in artificial intelligence with expectations of automation, efficiency, and competitive advantage. Yet many of these initiatives stall, underperform, or quietly disappear. What differentiates organizations that mature with AI from those that repeatedly struggle is not the absence of failure, but how failure is interpreted, governed, and learned from.

This article argues that AI failures should be treated not as individual or technical shortcomings, but as systemic signals. When examined without blame, they reveal deeper issues in strategy, structure, incentives, and decision-making. Learning from AI failures requires shifting from a fault-finding mindset to a capability-building one.

>> Click here to explore our webinar: Why Your Enterprise AI POCs Keep Failing and How to Fix It!

1. The Normalization of AI Failures

AI operates at the intersection of technology, data, people, and process. Failure, therefore, is not an exception but an expected outcome when any of these elements are misaligned. Early-stage AI projects often fail due to data quality issues, unclear objectives, unrealistic timelines, or weak integration with existing workflows. At later stages, failures tend to emerge around governance, scalability, explainability, and organizational trust.

The problem is not that AI fails, but that organizations frequently treat failure as an anomaly rather than a diagnostic tool. In many environments, failure triggers defensive behaviors: teams minimize issues, shift responsibility, or quietly decommission systems without extracting lessons. This response creates a cycle where similar mistakes are repeated under different project names. Normalizing AI failure as part of organizational learning is a prerequisite for long-term success. This does not mean lowering standards or tolerating poor execution. It means acknowledging that AI systems surface structural weaknesses faster and more visibly than traditional IT initiatives.

2. Why Blame Is Counterproductive in AI Initiatives

Blame-based cultures are particularly damaging in AI contexts because AI development depends on cross-functional collaboration. Data engineers, domain experts, product owners, compliance teams, and business leaders all contribute to outcomes. When a model underperforms or a system fails in production, assigning blame to a single role oversimplifies reality and discourages transparency. Blame also distorts feedback loops.

Teams may avoid reporting model drift, bias signals, or edge-case failures if they fear reputational or career consequences. This leads to delayed intervention, higher operational risk, and erosion of trust in AI systems. More critically, blame prevents organizations from asking the right questions. Instead of examining whether the problem was poorly framed, whether incentives were misaligned, or whether governance was insufficient, attention is diverted to individual execution errors. Over time, this weakens institutional learning.

3. Common Patterns Behind AI Failures

While AI failures manifest differently across industries, several recurring patterns appear consistently. There are four pattern we should focus on that allows leaders to treat failures as signals of systemic gaps rather than isolated mistakes.

3.1 Problem Misidentification

The first pattern is problem misidentification. Many AI projects begin with a solution in search of a problem. Organizations adopt AI because it is strategically fashionable, not because a specific, measurable business challenge requires it. As a result, success criteria are vague, and failure becomes difficult to define until resources are exhausted. Problem misidentification in AI projects not only leads to wasted resources but can also create a lack of focus and direction within teams. When organizations pursue AI initiatives driven primarily by trends rather than genuine business needs, they may overlook critical factors such as stakeholder requirements, user experience, and integration challenges.

This misalignment can result in poorly designed systems that fail to deliver meaningful value or improve operational efficiency. Furthermore, the absence of clear metrics for evaluating success often means that teams cannot learn from their failures, perpetuating a cycle of misguided efforts and reinforcing the belief that AI is inherently unreliable or unhelpful. Ultimately, this misidentification detracts from the transformative potential of AI, preventing organizations from fully harnessing its capabilities to solve real-world problems.

3.2 Data Optimism

The second pattern is data optimism. Teams often assume that data can be cleaned, labeled, and structured more easily than reality allows. Legacy systems, fragmented ownership, and poor data governance introduce friction that delays or derails projects. When models fail to perform, the root cause is often data readiness rather than algorithmic sophistication.

Data optimism can lead organizations to underestimate the complexity and effort required for effective data preparation. Many teams enter AI projects with the expectation that existing data is sufficient and can be readily transformed into actionable insights. However, they often confront challenges such as incomplete datasets, inconsistencies, and biases that require extensive cleaning and curation.

Additionally, without a robust data governance framework, issues like data silos and lack of collaboration can exacerbate these challenges. This false sense of confidence not only sets unrealistic timelines but can also result in frustration when expected outcomes are not achieved. Consequently, teams may mistakenly attribute performance issues to their models rather than recognizing the underlying data quality concerns, ultimately hindering their ability to leverage AI effectively for decision-making and innovation.

3. Organizational Disconnect

The third pattern is organizational disconnect. AI systems are built in isolation from the teams expected to use them. Without early involvement from end users, systems fail to align with real workflows, leading to low adoption even when technical performance is acceptable. Organizational disconnect can create significant barriers to the successful implementation of AI solutions. When development teams operate in silos, working independently from end users and stakeholders, they often lack critical insights into the day-to-day challenges and requirements of those who will ultimately utilize the systems. This disconnect can result in AI tools that, despite their technical capabilities, fail to address practical needs or fit seamlessly into workflows.

Furthermore, without user feedback during the design and testing phases, organizations risk developing features that are underutilized or even counterproductive. The resulting lack of engagement can lead to skepticism about the AI system’s value, further impeding its integration into the existing operational landscape. To overcome this disconnect, fostering collaboration and communication between technical teams and end users from the outset is essential, ensuring that AI solutions are intuitive, relevant, and beneficial for all parties involved.

4. Governance Lag

The fourth pattern is governance lag. As AI systems scale, issues around explainability, compliance, and accountability become critical. Organizations that delay governance until after deployment often face regulatory, ethical, or reputational setbacks that force abrupt shutdowns. Governance lag can significantly undermine the sustainability and trustworthiness of AI initiatives. When organizations prioritize rapid deployment over establishing robust governance frameworks, they expose themselves to a myriad of risks, including non-compliance with emerging regulations and ethical standards. This oversight often leads to challenges in ensuring transparency and accountability, making it difficult to explain the decision-making processes of AI systems to stakeholders.

As concerns around bias, privacy, and data security grow, organizations may find themselves scrambling to implement governance measures post-deployment, which may not only be resource-intensive but can also disrupt operations. Such reactive approaches can damage reputations, erode customer trust, and result in costly penalties, highlighting the importance of integrating governance considerations early in the AI development lifecycle. By prioritizing governance from the outset, organizations can foster a culture of responsibility and ensure their AI solutions are not only effective but also ethically sound and aligned with regulatory requirements.

4. Reframing Failure as a Learning Asset

Organizations that learn effectively from AI failures share a common trait: they reframe failure as structured feedback. Instead of asking who failed, they ask what assumptions failed. This reframing begins with post-implementation reviews that go beyond technical metrics. Model accuracy and latency matter, but they are insufficient. Effective reviews examine whether the original business hypothesis was valid, whether decision rights were clear, and whether the system changed outcomes in practice.

Learning-oriented organizations document these insights and feed them into future initiatives. Over time, this builds an internal knowledge base that reduces repeated errors and accelerates maturity. AI capability becomes cumulative rather than episodic. Crucially, this process requires psychological safety. Teams must feel able to surface issues early and honestly. Leadership plays a decisive role here by signaling that transparency is valued more than superficial success.

5. The Role of Leadership in Learning From AI Failures

Leadership behavior strongly shapes how AI failures are interpreted. When executives treat AI as a black box delegated entirely to technical teams, failures are framed as engineering problems. When leaders remain engaged with objectives, trade-offs, and risks, failures are seen as strategic learning moments. Effective leaders ask disciplined questions: What decision was this system meant to support? How was success defined? What constraints were underestimated? What signals did we ignore? These questions shift focus from outcomes alone to decision quality.

Leaders also set incentives. If teams are rewarded solely for launching AI systems rather than for delivering measurable impact, failure analysis becomes performative. Conversely, when incentives reward learning velocity and risk management, teams are more likely to surface and address problems early.

7. Building Structures That Capture Lessons

One effective mechanism is the establishment of AI review boards or steering committees that evaluate projects at predefined stages. These bodies assess not only progress but also assumptions, risks, and readiness to scale. When projects fail or pivot, insights are formally recorded.

Another mechanism is standardized documentation. Clear records of data sources, modeling choices, ethical considerations, and deployment constraints make it easier to understand why systems behaved as they did. This documentation becomes invaluable when teams change or systems are revisited.

Training also matters. Organizations that invest in AI literacy across management and non-technical roles are better equipped to interpret failures constructively. When stakeholders understand AI limitations, failure becomes expected and manageable rather than surprising and destabilizing.

8. From Isolated Failures to Organizational Maturity

Over time, organizations that systematically learn from AI failures develop stronger intuition about where AI adds value and where it does not. They become more selective in use cases, more realistic in timelines, and more disciplined in governance. This maturity manifests in several ways. Projects are smaller and more focused at inception. Data readiness is assessed honestly. Deployment plans account for human adoption, not just technical integration. Governance frameworks evolve alongside systems rather than trailing them. Importantly, failure rates do not necessarily disappear, but the cost of failure decreases. Each setback contributes to institutional knowledge that improves subsequent initiatives.

Conclusion: Failure as a Strategic Resource

AI Failures are inevitable in any organization seriously engaging with artificial intelligence. The question is not whether failures will occur, but whether they will be wasted or leveraged. Organizations that default to blame lose trust, slow learning, and repeat mistakes. Those that treat failure as structured feedback build resilience, capability, and long-term advantage.Learning from AI failures without blame requires leadership commitment, cultural discipline, and institutional mechanisms. It demands humility about what AI can and cannot do, and rigor in how decisions are made and reviewed. When failure is approached in this way, it becomes not a liability, but a strategic resource for building sustainable AI capability.